Managed Aquifer Recharge (MAR) is increasingly discussed in Europe as one possible measure to address water scarcity and to support more circular water management, but its role is far from settled. There are legitimate open questions about the long‑term fate of emerging contaminants such as PFAS and pharmaceuticals, cumulative impacts on groundwater‑dependent ecosystems, and the robustness of MAR schemes under deep climatic and socioeconomic uncertainty. A neutral assessment has to acknowledge both the technical possibilities and these unresolved issues.

The MARCLAIMED project, with demonstration sites in Spain, Portugal and the Netherlands, offers a structured basis for such an assessment. MARCLAIMED analyzes under which conditions MAR can function technically, which non‑technical factors constrain implementation, and what kinds of digital and governance infrastructures are needed to evaluate MAR options rigorously alongside alternatives. This article summarizes those insights and discusses how data‑centric tools provided by EGM support evidence‑based decisions—whether the outcome is to implement MAR, redesign it, limit it, or decide against it in specific contexts.

MAR’s Potential and Its Uncertainties

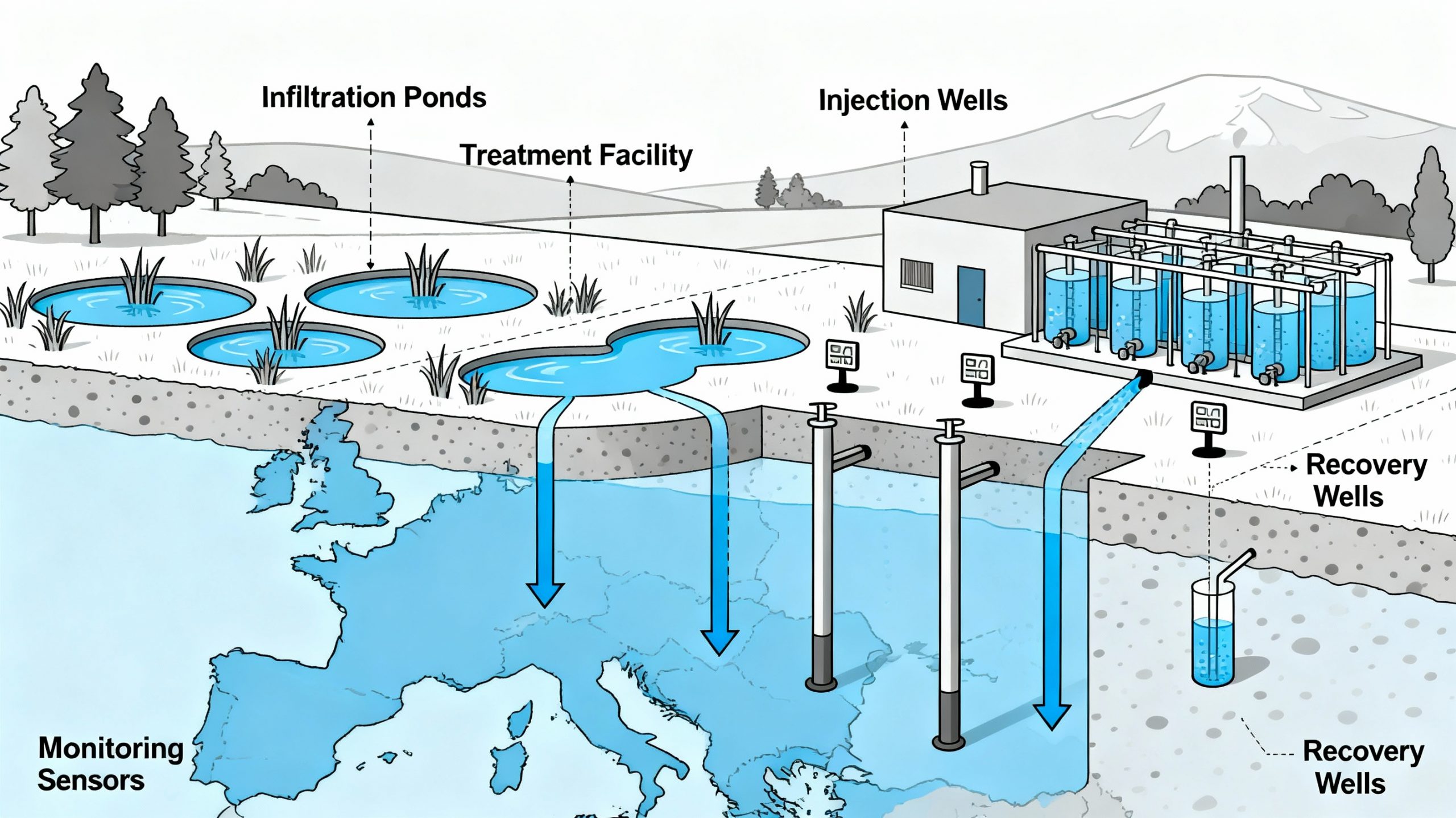

Under favorable hydrogeological and operational conditions, MAR can provide three functions. It can increase effective storage by using existing aquifer capacity, sometimes avoiding the footprint and evaporation losses of new surface reservoirs. It can buffer temporal variability by storing water from wet periods or surplus treated wastewater for later use in dry periods. And it can interact with other measures, such as wastewater reuse or agricultural drainage management, in more integrated circular water systems.

The MARCLAIMED demonstration sites illustrate these possibilities in concrete settings. In the Baix Llobregat near Barcelona, infiltration ponds and an injection well introduce reclaimed and pre‑treated surface water into coastal aquifers to help stabilize groundwater levels and reduce saltwater intrusion. In Comporta, Portugal, soil‑aquifer treatment linked to a wastewater treatment plant explores the potential to improve water quality during underground residence. On Texel in the Netherlands, agricultural tile drainage water is stored underground using an Aquifer Storage, Transfer and Recovery (ASTR) configuration to increase local freshwater availability for farming. These cases show that MAR can be engineered to operate, but they are site‑specific experiments rather than blueprints for general replication.

At the same time, several critical aspects remain incompletely understood. For emerging contaminants, including PFAS and a broad group of contaminants of emerging concern (CECs), treatment trains and natural attenuation may reduce concentrations, but long‑term behavior and potential accumulation in heterogeneous aquifers are not fully characterized over multi‑decadal horizons. Laboratory and short‑term field data exist for some compounds yet extrapolating to complex real‑world systems remains uncertain. Similarly, ecological impacts—on groundwater‑dependent ecosystems, stream–aquifer interactions, and subsurface microbial communities—can vary markedly across sites and often depend on subtle changes in hydrology and chemistry.

Cumulative and long‑term risks are also difficult to isolate. MAR interacts with ongoing abstraction, land‑use change, and climate‑driven shifts in recharge and demand. A scheme that appears beneficial under current conditions could interact differently with a future regime characterized by more frequent droughts, altered recharge patterns, or new contaminant sources. Finally, robustness under “deep uncertainty”—where future climate, regulation and behavior cannot be assigned reliable probabilities—cannot be established by a single deterministic scenario. These uncertainties do not imply that MAR should not be used, but they argue for a cautious, adaptive and comparative approach in which MAR is assessed alongside other options such as demand management, desalination, changes in allocation and storage operation, and even explicit acceptance of certain scarcity levels.

Non‑Technical Factors That Shape Feasibility

One of MARCLAIMED’s main findings is that, in many European contexts, MAR deployment is constrained less by recharge or treatment technologies than by regulation, governance, economics and data availability.

On the regulatory side, MAR sits at the intersection of groundwater protection, water reuse, drinking water regulation and environmental flow requirements. Multiple agencies often share authority: health services, water agencies, environmental regulators and local governments may all need to approve MAR operations, and they may have different interpretations of acceptable risk, particularly for emerging contaminants.

Economic and financial alignment presents another set of constraints. MAR infrastructure typically requires significant upfront capital outlays for recharge basins or wells, pre‑treatment, and monitoring, while many of the benefits arise in exceptional conditions, for example during severe droughts, rather than in average years. This temporal mismatch makes MAR difficult to justify within conventional utility investment horizons. In addition, the distribution of costs and benefits is often uneven. Farmers may benefit from supply security but have limited capacity to co‑finance capital expenditures; urban users may be asked to support MAR through tariffs without perceiving a direct gain; ecological benefits such as reduced saline intrusion or improved baseflow are diffuse and not priced. Current European tariff systems, shaped by the Water Framework Directive’s cost‑recovery principle and affordability limits, already struggle to fully cover existing services. Adding MAR on top of under‑recovered systems without revisiting tariff design, subsidies and cross‑sector contributions is therefore challenging.

Social perception and acceptance add a further dimension. Research under MARCLAIMED and earlier projects indicates that perceptions of health risk are central, particularly for MAR using reclaimed wastewater, even when standards are met and risk assessments are favorable. These concerns are influenced by incomplete knowledge about long‑term contaminant behavior and by general caution regarding new uses of treated wastewater. Trust appears to depend more on transparency, continuous monitoring and perceived community control than on technical explanations alone. Different groups—farmers, urban residents, environmental organizations, industries—begin from different values and tolerances for risk and cost, so convergence on a single view cannot be assumed. This suggests that acceptance is a structural factor in feasibility, not an afterthought to be addressed only at communication stage.

The Central Role of Data Integration

A less visible but equally important constraint identified in MARCLAIMED is data fragmentation. In a typical basin, hydrogeological data are managed by groundwater authorities or research institutions, wastewater treatment plants run their own SCADA systems, drinking water providers maintain separate operational and quality records, agricultural organizations track irrigation and drainage, and environmental agencies monitor flows and ecological indicators. These datasets use different formats, spatial references, time steps and semantics, and they are seldom integrated.

This fragmentation complicates all stages of MAR assessment. Establishing a robust baseline and counterfactual—what would likely happen without MAR—requires hydrological and water‑use data that are consistent and accessible across institutions. Comparing MAR to alternatives, such as desalination or demand management, under common climate and demand scenarios depends on the ability to feed consistent data to multiple models. Adaptive management, which is particularly important given uncertainties around contaminants and long‑term behavior, depends on systematic monitoring and timely feedback into decision‑making, which is difficult when data are scattered across organizations and formats.

A neutral, evidence‑centered approach therefore requires not just more data, but better architecture for data use. This includes integrated monitoring strategies that link flows, levels, quality and costs through shared standards; interoperable data exchange interfaces, such as NGSI‑LD, that make it unambiguous what a given variable represents and under what conditions it was measured; analytical workflows that connect hydrological, economic, regulatory and social analyses; and clear access policies that balance confidentiality with the needs of regulators, affected communities and researchers to inspect and question evidence.

How Data Platforms Can Support Neutral Decision‑Making

EGM’s work across water, agriculture, smart territories and risk management is centered on capturing, normalizing and analyzing data, and this capability is directly relevant for MAR and other circular water strategies. In these contexts, the primary value of such tools is not to push a pre‑defined solution but to clarify where evidence exists, where it does not, and how alternative options compare under different assumptions.

At the capture stage, a basin‑scale data platform ingest heterogeneous streams from field sensors, SCADA systems, laboratory results, administrative records and survey instruments. This includes groundwater levels and chemistry, flows and quality at wastewater treatment plants, surface water discharges, energy and cost data, and indicators of social perception. Automated ingestion pipelines with consistent timestamps and spatial references permit near‑real‑time updates without forcing existing systems to be replaced. Basic validation and anomaly detection help make data quality issues visible rather than hidden in background noise.

At the processing stage, normalization and semantic enrichment are critical. Units, coordinate systems, naming conventions and temporal resolutions need to be harmonized, and key concepts—such as recharge volume, nitrate concentration or unit cost—are represented in a semantic model that indicates units, methods, uncertainty and provenance. This is where NGSI‑LD and similar approaches are useful, because they allow different tools and organizations to interpret data consistently. Data governance rules can be encoded at this level, distinguishing between public information, restricted information for authorized users and strictly confidential data, so that cross‑actor analyses become possible without uncontrolled disclosure.

At the analysis stage, such a platform becomes the backbone for combining hydrological and hydrogeological models, water quality and transport simulations, economic tools like MARINSURE and RECOVER, and social models or acceptance indicators. Decision‑makers can explore scenarios such as: under a given climate projection, with a specific MAR design and treatment train, and a particular tariff and subsidy structure, how do groundwater levels, costs and contaminant profiles evolve over 20 years, and how do these outcomes compare to those produced by alternative measures? Uncertainties in inputs and models can be propagated explicitly rather than ignored, allowing stakeholders to see not just central estimates but ranges of plausible outcomes.

Crucially, such tools do not reduce complex decisions to a single prescribed answer. They help articulate “it depends”—showing how conclusions change with different assumptions, and which uncertainties matter most. In the context of emerging contaminants like PFAS, for example, they can highlight where knowledge gaps about sorption, degradation or by‑products in specific lithologies significantly affect risk estimates, informing monitoring priorities and caution levels without claiming more certainty than the data support.

Governance for a Cautious and Adaptive Approach

Given MAR’s potential and its uncertainties, governance frameworks that emphasize caution, adaptability and comparison with alternatives are appropriate. MARCLAIMED’s experience suggests several directions without prescribing a single model.

At the regulatory level, European and national guidance could explicitly recognize uncertainty, especially for emerging contaminants and ecological impacts, and structure MAR authorization as an adaptive process rather than a one‑time approval. This would include time‑limited permits conditioned on monitoring and periodic review, with clear provisions for adjustment if unexpected effects are detected, and for learning across sites. Harmonizing key definitions and expectations across water reuse, groundwater protection and drinking water regulation would also lower interpretive barriers.

In planning, MAR should be treated as one option in a portfolio of measures rather than as a default solution. Basin‑scale planning processes can use integrated modeling to compare MAR, demand management, alternative supplies and policy changes under multiple climate and demand scenarios, making explicit the trade‑offs in cost, risk, environmental impact and distributional consequences for different user groups. Such portfolio analysis aligns better with the reality that no single measure will address all risks in all basins.

Institutionally, investments in shared data infrastructure and in Communities of Practice can support coordinated learning. MARCLAIMED’s co‑creation work points to the value of involving utilities, regulators, farmers, municipalities and civil society actors early in the design and assessment of MAR and other options, supported by accessible visualizations and transparent data. This helps align expectations and build trust not on assurances but on shared access to evidence and acknowledgment of remaining uncertainties.

Conclusion: Evidence Before Enthusiasm

Managed Aquifer Recharge is one tool in Europe’s evolving response to water scarcity and variability. It has technically demonstrated capabilities in specific contexts, but also meaningful scientific and governance uncertainties, particularly around long‑term contaminant behavior, ecological interactions and robustness under deep uncertainty. A neutral stance neither promotes nor rejects MAR in the abstract; it insists that decisions be based on the best available evidence, that remaining uncertainty be made explicit, and that MAR be evaluated in fair comparison with other measures.

Digital platforms like those developed by EGM cannot resolve these uncertainties on their own, but they can make them visible and manageable: by integrating fragmented data, by supporting transparent multi‑model analyses and by enabling stakeholders to interrogate assumptions and results. Whether a basin ultimately chooses to implement MAR, redesign it, restrict it to certain uses or not pursue it at all, decisions grounded in shared, well‑documented evidence are more likely to be legitimate, technically robust and adaptable as new knowledge emerges.